All year round I can hear church bells ringing, if I happen to be out in my garden on a Wednesday evening.

Every week without fail a dedicated group of locals gather to chalk their palms and tug vigorously on the colourful fluffy woollen sallies, which dangle at the end of flaxen bell ropes (try reading that sentence without imagining Harry Hill doing his his famous ‘look to second camera with raised eyebrows’ bit).

Those ringers though, they really go like the clappers of hell some nights, must be thirsty work!

There’s long been a relationship, albeit sometimes a testy one, between The Church and The Pub in Britain, going back to at least the late medieval era.

Back then inns and taverns were closely associated with the church, and existed to see to the needs of travelling clergy, pilgrims and the various craftsmen engaged in gargoyle sculpting, etc.

During the English Reformation, some of the more puritanical forces had put a stop to papist churches brewing up Whitsun and other church ales, which their parishioners would consume over the course of a week or two, to celebrate various points in the festive calendar, as a fund-raising initiative.

To plug this gap in the market, alehouses began to spring up, turning the joint enterprises of eating, drinking and being merry from a seasonal, and largely clerically controlled treat into an all-year-round free for all, much to the chagrin of the Calvinist fun police.

Those morality enforcers would go on to enact legislation requiring this particular iteration of the public house to apply for a license from the magistrate to sell their intoxicating brews, inns and taverns being largely exempted at this point.

Even today, many centuries later (plus a few skirmishes and disputes over which divine authority we thought ought to guide us as a nation, before we settled into the largely secular society we now are) the thread that wove together the fates of these two institutions can still be felt, particularly in more rural settings, where the appetite for toasting older gods never really went away.

Since that time, both church and pub have functioned in some form or another as twin pillars of communion, and are often the keystone species used to exemplify Merrie Olde England in the literature.

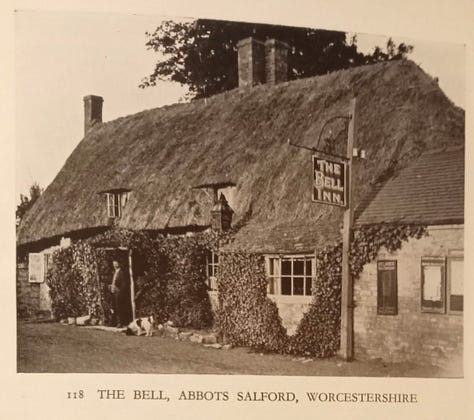

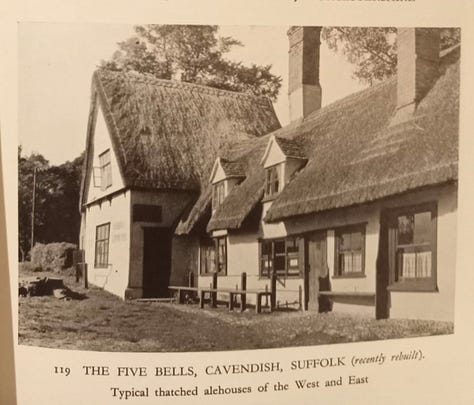

More recently, you can find this pairing at its most emblematic in the illustrations of Batsford book collections such as the Old Inns of England or The Face of Britain series, and such like.

In fact the Old Inns of England notes that: “The tradition of centuries is not lightly disturbed, and these alehouse parlours are as intimately connected with the history and fortunes of their villages as are even the manor-houses and the churches.”

So, Church and Pub; indisputably the dual facets of our core national identity for much of the last millennia, and a perfect marriage of the sacred and the profane.

They are two realms that had, for most of the modern era, held the tension between our public lives and our private selves; our moral and spiritual aspirations in contrast to our more corporeal wants and needs.

One exists to feed the soul, the other to fill a hole, if we’re really getting down to brass tacks.

The relationship is all very characteristic of us as a nation; pious ostentation with a hearty side-order of hedonism. Sparing no expense in crafting ornate and imposing places to host our heavenly devotion to god-fearing, all the while cobbling together slightly less palatial but far more numerous temples of inebriation.

Reverence vs revelry. The duality of man.

Nowadays, when in close proximity, they often form a symbiosis where their functions overlap. Many a wedding or christening ceremony’s attendees, or funeral cortege, for example, will head straight from the church pews to the nearest pub settles, should the opportunity present itself.

I would hope those hard-working bell-ringers, who fill the air of my village and its surrounds with their midweek peals, get a well earned libation for their efforts at a nearby watering hole!

Many churches in Britain will have had at least one pub within spitting distance of their yew-lined perimeters at some point. A licensed establishment’s proximity to one of these monuments to the numinous has, in many cases, given rise to pub names which denote the audibility of the latter’s calls to prayer.

A couple of villages over from mine, in the splendidly named Hinton Blewett sits the ancient church of St Margaret’s, which shares a party wall with the aptly named village pub The Ring O’Bells. A pub I’ve happily filled my own hole in, many times.

Any ringers seeking to purge the dusty dryness from their throats, wrought from an evening of earnest clanging at this church need only hop the boundary wall, and all of their pint-based prayers are answered.

It’s now a genuine free house, since longtime licensees the Bennetts bought it outright in 2024. They run it with a tangible sense of love and pride for what they do, and I’d recommend it for the beautiful and extensive views of the Cam Valley alone, as seen from the ridge crest of the Mendip plateau which the pub occupies. Views that are, in my experience, best enjoyed on a sunny autumn afternoon, over a crisp pint of Gorge Best and one of their delicious burgers.

A few miles away, in the nearby village of Compton Martin, you can find another pub sporting the Ring O’Bells moniker. Not a free house like it’s Hinton Blewett namesake, this Ring O’Bells (or ‘The Ringer’ as it’s locally known) is owned by the Butcombe Group.

Up until recently, you might have found yourself enjoying a pint and an intimate Coldplay gig, or a quiz hosted by Kylie at the Ringer. That’s because up until recently one of the tenants was also music industry legend Miles Leonard; then chairman of Parlophone records / Warner music.

Unfortunately for Miles, when the equally legendary Bristol-based Butcombe Brewery was merged with Jersey’s Liberation Ales, and both got subsumed by new owners Caledonia Private Capital into umbrella company Liberation Group (since renamed Butcombe Group) he and his business partners in the pub soon found themselves being liberated from the terms and conditions of their tenancy agreement.

After weathering two lockdowns during nine years of trading, and having turned the fortunes of what was a fusty and failing boozer around, creating a hip and happening, thriving pub beloved of local and visitor alike, Mr Leonard and associates were given notice of the pub company’s intentions to bring the business back into their managed estate, unless the incumbent tenants were willing to shoulder a rent increase of over 100%, as well as an increase in their spending with the brewery to a similar tune.

This obviously untenable situation sounded the death knell for Leonard et al’s occupancy, and they threw in the bar towel. The pub was handed back to the company, despite a thousands-strong petition against the move, and an attempt by the parish council to secure an Asset of Community Value order on the business, to continue operations as was. All sadly to no avail.

The company took back control, with the bar manager being retained after the Leonard’s departure, to provide some continuity. While the pub still appears for now to be a thriving hub of local and visitor trade, it’s a safe bet that its ongoing success is still very much riding on the coattails of what was built by Miles, and the work he and his associates put in during their tenure.

My own village, Temple Cloud had a Bell Inn way back when the main road functioned as a turnpike. It’s a residential building these days, and a handsome one at that, which is now known as The Refuge. It’s fairly likely that the bell which this establishment was named in acknowledgement of is the one at the notably historic church of St James, in nearby Cameley. Nicknamed a ‘Rip Van Winkle’ church by Sir John Betjeman in his Collins Guide to English Parish Churches, it has remained largely unaltered since it was founded in the twelfth century.

Onwards, and keeping slightly with an ecclesiastical theme, there’s The Bell Inn at Hornden-On-The-Hill in Essex. This pub has retained the tradition of hanging a hot cross bun from the rafters every Easter, since the ritual was begun there over one hundred years ago.

The origins of this strange habit aren’t entirely known but it’s supposed that the Landlord who started it had taken the tenancy over on a Good Friday, and so celebrated by suspending a starchy symbol of the crucifixion from the ceiling. Everyone’s got to have a hobby, I suppose!

By all accounts it’s not the only pub to oversee this odd ceremony, and there’s some suggestion that the retention of one bun from each year’s batch was a more general practice in days of old, since it was not only believed that goods baked on this day were imbued with magical properties, and wouldn’t spoil, but that keeping one back would carry over that year’s luck into the next.

During the food-rationed war years, when baking ingredients were in shorter supply, the tradition continued through the use of other materials. You’ll therefore find wooden and concrete ones dangling next to the standard issue dough-based confections. Hopefully those ones have been anchored a bit more firmly to the beam, as you’d certainly get your bell rung if one became unmoored mid-session.

It’s not all God-adjacent campanology that influences the naming of pubs in this genre. Some are so-called in homage to bells in their floral form. Campanulas aka Canterbury Bells have a rich folkloric symbolism which is often referenced in pub names.

One such example hit the headlines when the brewery who own The Eight Bells in Kent decided to spruce up the pub’s old sign, which featured a maiden’s face framed by a stalk of eight bell flowers.

The landlady couldn’t believe the faux pas when the sign makers who, having been commissioned to re-image the pub’s livery, returned a shiny new sign showing their interpretation of the inside of Canterbury Cathedral’s bell tower.

Not only had they failed to depict the original floral connection to the pub’s name, but what they had designed inaccurately showed a bell tower complete with eight bells of the metal variety! An honest mistake given that the number of bells in a pub name usually corresponds to the number of bells in the nearest bell tower. Canterbury Cathedral’s Harry Bell Tower famously only has one. They really dropped a clanger there! (I’m not even sorry for that one).

Bell themed pubs are numerous - too numerous to list here, but a few more famous examples would have to include:

The Ten Bells, Spitalfields - said to have been frequented by several of Jack the Ripper’s victims; and firmly on the map of modern day extremely tasteful and respectful Ripper tours, since the discovery of the final known victim, Mary Kelly (having been found deceased on the opposite side of the road to the pub in November of 1888) seemed to draw a line under the despicable slayings.

The Bow Bells - a legendary East End boozer, and a monument to all things orange and all things cockney.

The Bell Inn, Nottingham - ancient inn, and in the running as potentially the oldest Inn in Nottingham, facing some pretty stiff competition for that title from the likes of Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem, and Ye Olde Salutation Inn.

The Bell Inn, Bath - a rockstar-backed, community supported pub partially bankrolled by the likes of Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and former Genesis frontman Peter Gabriel. Another example in a growing trend of patrons understanding the principle of use it or lose it.

Finally it’s worth mentioning The Blue Bell, Flintshire.

Pete Brown wrote an excellent book which functions almost like a directory of the 250 best boozers in the land, according to him. For the avoidance of confusion, he called this encyclopaedic tome ‘The Pub’. In it, he dedicates an entire page to this particular pub, putting emphasis on the altruistic nature of its licensees and its punters.

A free house situated at the top of Halkyn mountain, this pub sits among a small community of Welsh hill farms, whose sheep graze the common land there. The information in this book may now be slightly out of date, since it was published almost a decade ago, and changes happen fast in the pub world, but a quick check on Trip Advisor reveals high ratings up to the present day.

In the book’s entry, Pete Brown details an event that takes place every few months on a Saturday night, advertised as a ‘Cheese and Pickled’ night. The pub doesn’t do food since it allowed the post office to function from what was its dining area, so instead it holds this event periodically for the locals. The idea is that while the pub provides the hardware, and the bread and crackers, the regulars bring the cheese.

This is then divvied up into a communal resource, from which people help themselves. There’s no charge to attend this event, and the author marvels at the generosity of attendees, where they will often bring more than they take, as well as donate their own baked items for good measure.

It’s a prime example of the public spiritedness that has always been at the heart of small community pubs, and which bucks the trend of the more usual uniformity imposed by corporate overlords, which often kills them off like the fabled Golden Goose.

In his snappily-titled ‘An Itinerary; His Ten Yeeres Travell Through The Twelve Dominions Of Germany, Bohmerland, Sweitzerland, Netherlands, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turkey, France, England, Scotland & Ireland’ the 16th century travel writer and social commentator Fynes Moryson, being so inspired by the English custom of inn-keeping, despite exposure to what much of the northern hemisphere had to offer in terms of hospitality, felt moved to remark that: “the World affords not such Innes as England hath…”

On that resounding note, I’m ringing the bell to signal the end of this post.

That’s time!